“The Queen of Versailles” — Music and Lyrics by Stephen Schwartz. Book by Lindsey Ferrentino based on the documentary film “The Queen of Versailles” by Lauren Greenfield and the life stories of Jackie and David Siegel. Directed by Michael Arden. Scenic and Video Design by Dane Laffrey; Costume Design by Christian Cowan; Choreography by Lauren Yalango-Grant and Christopher Cree Grant; Music Supervised by Mary-Mitchell Campbell; Lighting Design by Natasha Katz; Sound Design by Peter Hylenski. Produced by Bill Damaschke, Seaview, and Kristen Chenoweth, through her production banner Diva Worldwide Entertainment. Presented by Emerson Colonial Theatre at 106 Boylston St., Boston through August 25.

By Shelley A. Sackett

There is no more perfect setting for a play about Versailles and consumerism gone awry than Boston’s own Colonial Theatre, with its gold, glitz, and Rococo splendor. On opening night last Thursday, the festive crowd for “The Queen of Versailles,” the Broadway-bound musical extravaganza, was dressed as if auditioning as contemporary cast extras with bling, boas, and bottles of champagne.

But that was nothing compared to Dane Lafrey’s lavish Louis XIV worthy set, thankfully on pre-curtain-rise display to accommodate selfies and elicit oohs and aahs.

On walls as tall as the Louvre hung oil paintings with ornate gold frames. Chandeliers descended, and palace workers dressed in period wigs and frocks went about their menial duties, dusting and fussing. The staff joked about the comical and pompous King Louis XIV (Pablo David Laucerica), who proudly admits he commissioned the Palace of Versailles “because I can.”

This first musical number primed the audience, and they were cocked and ready for the main attraction. When the royal set lifted along with the curtain, revealing Kristin Chenoweth seated on stage, they exploded into the kind of boisterous adulation reserved for, well, royalty.

From the get-go, it was evident the audience’s admiration was well-placed. Chenoweth is a pint-sized spitfire with super-sized talent. She belted out her first song in a clear, articulate voice that was perfectly projected. What a joy to be able not only to hear the lyrics but also to understand them. Stephen Schwartz’s score is smart, funny, and sharply satiric and deserves no less, especially since much of the action takes place in song. (Question for the production team — why no song list?).

In a nutshell, the show is about the riches-to-rags-to-resurrection story of Jackie and David Siegel, whose saga was the topic of Lauren Greenfield’s award-winning 2012 documentary by the same name. Its filming is where Act I opens.

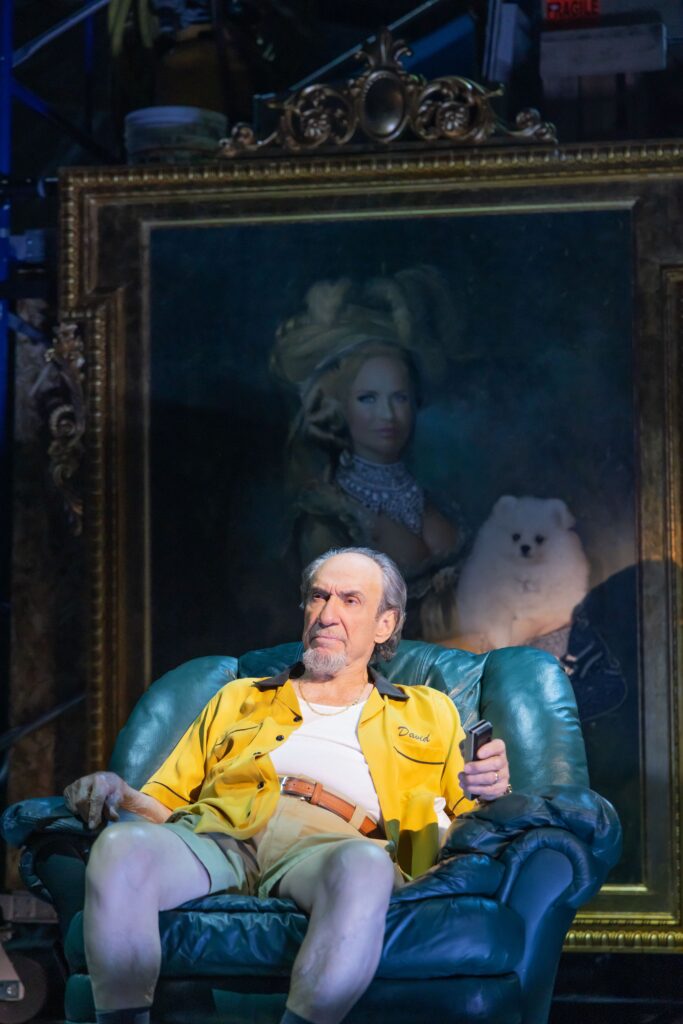

Clad in one of Christian Cowan’s sensationally tacky costumes, Jackie literally holds court in the midst of the construction site of her and time-share mogul husband David’s (a superb F. Murray Abraham) life-fulfilling project: building the largest private home in America.

Why are they building this 18-bedroom, $100 million home? It’s simple when you have champagne wishes, caviar dreams, and deep, deep pockets. “Because we can,” Jackie boasts, echoing her French idol.

Their 90,000-square-foot house is based on the mirrored palace with a few modifications: Versailles, France, is swapped for Orlando, Florida, and Queen Marie Antoinette has morphed into Jackie. In terms of pointed social commentary, especially since 2016, their story is particularly poignant, and the show milks it dry. “Anyone can become royalty in America,” is the Siegel family credo – or president, even.

Jackie takes us (as the documentarian’s camera rolls) backstage to her humble beginnings. She was raised in Endwell, New York, where she worked several minimum-wage jobs and honed her appetite for success and power at the encouragement of her simple and decent parents. The family’s favorite show was “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous,” which they watched together with near-religious reverence.

She earned a bachelor’s degree in computer engineering in 1989 and polished her gutsy in-your-face, tell-it-like-it-is style at her first job with IBM. Though Jackie may dress like an airhead, it masks underlying book and street smarts. Coupled with her cutthroat drive, she is a force to be reckoned with.

After moving to Florida with her husband, he becomes abusive, and she enters the Mrs. Florida America beauty pageant as a way out (she won), determined to make her pipe dream of great wealth come true. Following her divorce, the now single mom does just that when she meets and, in 2000, marries the financier and “Timeshare King,” David Siegel.

The two travel to France for their honeymoon dressed like Barbie and Ken (“This may surprise you, but we’re not old money,” David dead-pans). When Jackie goes gaga over Versailles, it mirrors every selfie-obsessed narcissist’s sex dream; David declares his ever-lasting devotion in the language that is the vernacular of their relationship: he will build one for her.

The rest of Act I (a hefty 90-plus minutes) details Jackie’s voracious appetite for children (she births 7 and adopts one more, her niece Jonquil) and things. The oldest daughter, Victoria, the product of Jackie’s first abusive marriage (a very good Nina White), is, in Jackie’s estimation, overweight and under-acquisitive. Her clueless mother is tone-deaf and blind to her daughter’s unhappiness. If anything, she adds to it. Jackie, the quintessential material girl who craves its empty calories, urges Victoria to curb her fondness for the one thing that comforts and nourishes her — food.

In Victoria’s solo (in which White shines), she describes the pain and heartbreak she suffers as her mother’s daughter. “Pretty always wins. The only way for me to win that game is not to play it,” she says.

Her sister/cousin Jonquil (Tatum Grace Hopkins), on the other hand, takes to excess like a fish to water. “I could get used to this,” she croons.

Act I closes in 2008, as the Siegel’s world comes crashing down alongside the global financial and subprime markets. Overnight, they go from prince to pauper, monitoring electricity with the same zeal they had reserved for padding their warehouses with stuff. David retreats to his study, demanding Jackie pull the plug on the documentary now that their lives have gone sideways. Jackie, however, has the soul of a phoenix and a cat’s nine lives. She’s not going down with the ship. As God is her witness, she will get her Versailles back.

Act II opens with one of the show’s musical highlights, a gorgeous duet with Jackie and Marie Antoinette (the fabulous Cassondra James). In a rare moment of acknowledging and really listening to Victoria, Jackie realizes the toll all this has taken on her. The girl is depressed and adrift. She needs some roots and parenting.

The two pay a visit to Jackie’s parents, who open Victoria’s eyes to a new world. For the first time, she sees that some people (her grandparents among them) are actually happy with what they have. They have found the magic of “enough.”

Although mother and daughter sing another lovely duet about little homes with big hearts, Jackie chides Victoria when she says she’d like to stay in Endwell. Jackie reminds her of what great wealth can buy, renewing her vow to get Versailles back. “Just because we can doesn’t mean we should,” Victoria says, sounding more like a parent than a child.

The Siegels ultimately regroup after their personal and financial setbacks, but they have paid a heavy price. They keep the unfinished Versailles and even manage to exploit Victoria’s tragedy, manipulating a spin to their own financial and marketing advantage. They are deplorable peas in a morally bankrupt pod, easily two of the least sympathetic characters we’ll ever meet on stage.

Yet, along with the glitterati in the audience, I too rose in a standing ovation, surprised by how much I had enjoyed the show.

Chenoweth is the little engine that can, relentlessly driving the show uphill when its length, digressions and sour message threaten to derail it. She is a prodigious talent and she brings it to bear on her portrayal of Jackie. We may want to dismiss the self-appointed queen as a crass example of the worst capitalism can spawn, yet Chenoweth’s nuanced portrayal leaves the door open enough to glimpse the shadow of admiration and sympathy. And boy, can she sing!

The rest of the cast is a star-studded who’s who of Broadway luminaries. One can only hope that the “Queen of Versailles” that reaches the Big Apple is leaner, more focused, and more deserving of the gifted artists and advance hype it has attracted. Many scenes (especially a cowboy-themed one) belong on the cutting room floor, as do a couple of the many flashbacks to King Louis’s days.

The show has great bones, an engaging score, and a tornado of a star. All it needs is disciplined tweaking, refining, and shortening before it travels south. It deserves to take Broadway by storm.

For tickets and more information, go to www.emersoncolonialtheatre.com.