“Yellow Face.” Written by David Henry Hwang. Directed by Ted Hewlett. Scenic Design by Szu-Feng Chen; Projections Design by Megan Reilly; Lighting Design by Baron E. Pugh; Costume Design by Mikayla Reid; Sound Design by Arshan Gailus. Presented by The Lyric Stage Company of Boston, Clarendon St., Boston. Run has ended.

By Shelley A. Sackett

Some plays are just good for you. Like drinking a peanut butter, kale, bone meal, and flax seed smoothie, the benefits outweigh the temporary discomfort. With the smoothie, its promise of increased vigor and decreased ailments offset its taste and texture. With “Yellow Face,” David Henry Hwang’s Obie award-winning play presented by The Lyric Stage Company of Boston, its thought-provoking and post-theater-conversation-inducing messages outweigh the lackluster nature of its two-hour theatrical experience.

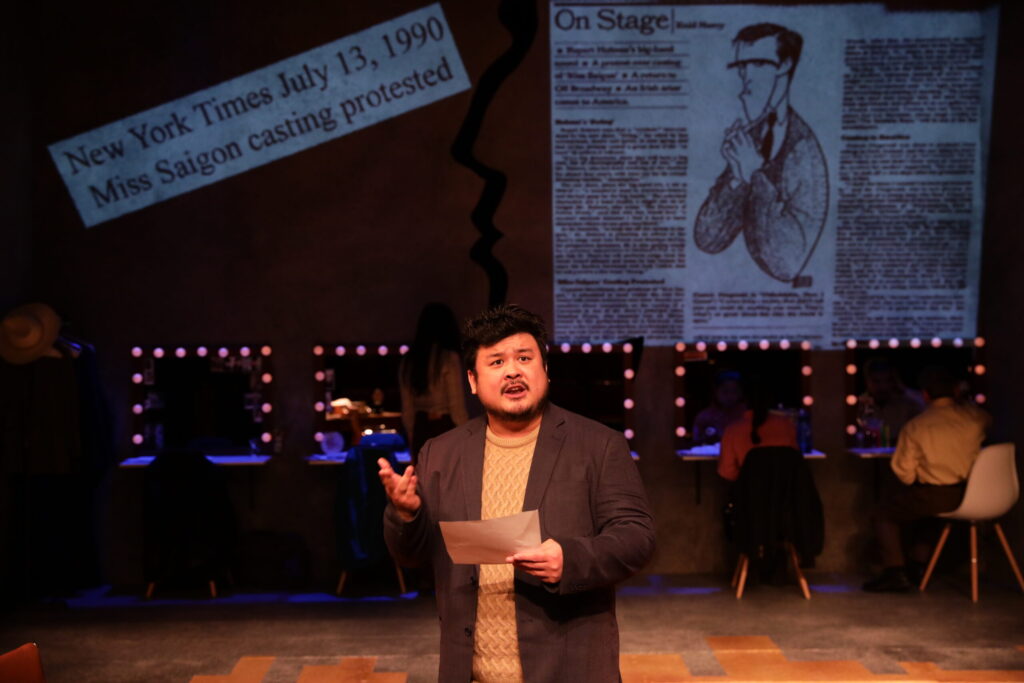

Hwang has a lot to share. Wading through the weeds of his self-deprecating, semi-autobiographical plot is a bit of a slog. It all started in 1990 when the white Welsh actor Jonathan Pryce was cast as the French-Vietnamese star of the smash Broadway hit, “Miss Saigon.” (Note: Hwang’s 1988 Tony award-winning hit, “M. Butterfly” was inspired by the same Puccini opera, “Madame Butterfly.”)

Hwang condemns this casting choice as a form of “yellowface.” He becomes the standard-bearer of the New York Asian-American theater community’s protest, demanding that Actors Equity join them. After much public waffling, Actors Equity backs the choice of Pryce and the play goes on to be a smash hit.

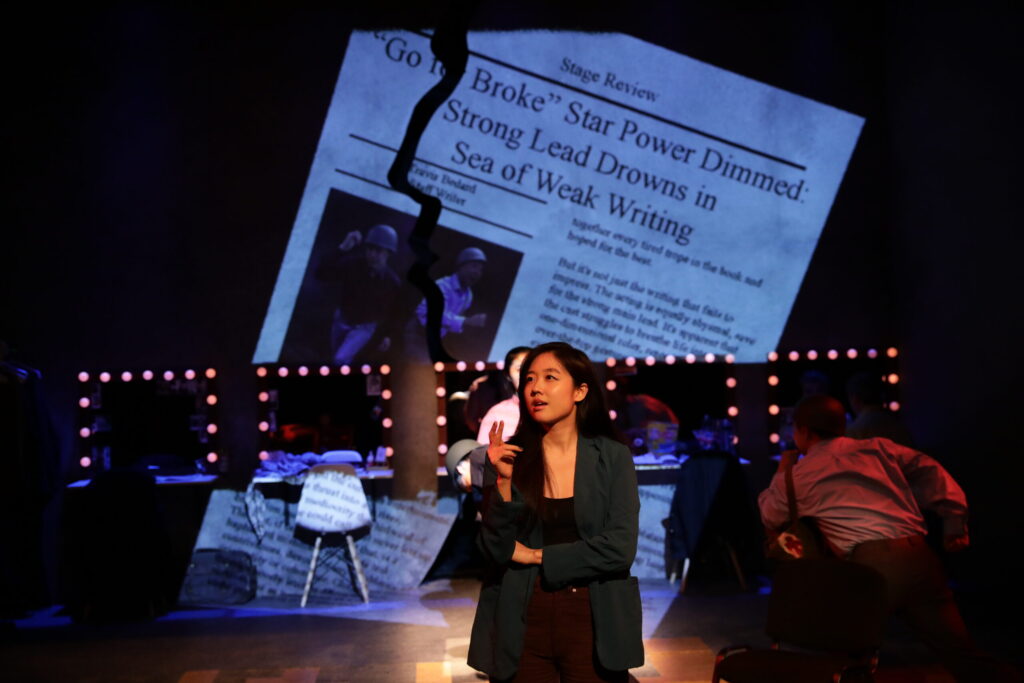

Outraged, Hwang pens the colossal flop, “Face Value,” a hard-edged comedy about casting white actors as Asians. In an oversized karmic boomerang twist, Hwang commits the ultimate ironic faux pas — he casts a white actor, Marcus G. Dahlman, to play its Asian lead.

Rather than admit his mistake, eat crow and move on, Hwang compounds the error by revisioning Dahlman’s ancestry and giving him the more Asian last name, Gee. In a fit of twitchy pique, Hwang then fires Gee, who earns praise and fortune playing other Asian roles, including the King in “The King and I.”

Hwang, a “real” Asian, is, by contrast, broke and eking out a tough existence as a playwright. To his later detriment, he even accepts a position on the board of directors at his father’s bank.

We witness a metamorphosis in Gee as he emerges from his “fake” Asian cocoon to spread his butterfly wings. Gee genuinely identifies as a member of the Asian American community and longs to be accepted as a full-fledged member. He becomes an activist and supporter of Asian American values. He even dates an Asian American (Hwang’s ex, no less). He wears his Asian identity so effectively that when the U.S. Department of Justice and various congressional committees charge Asian Americans with aiding the Chinese government in election interference, Gee is among those named.

Act II is where Hwang exercises a little more self-discipline, honing in on the rabbit hole of weighty philosophical, political, moral, and semantic issues that surround discussions about race. He abandons Act I’s “poor me” tirades and tackles meatier topics. Like the health effects (vs the taste) of that muddy smoothie, it is worth the wait.

Hwang is unafraid to ask the big questions. What, for example, is “cultural authenticity?” What does it mean? More importantly, what does it matter? Is the very idea of cultural authenticity racist? Where exactly is that tipping point between artistic legitimacy and discrimination?

“The face you choose to show the world determines who you really are,” Gee says, quoting an ancient Chinese saying. Yet, when that face is Caucasian — no matter how much the heart beats as Asian — who are we looking at? Which is more ambiguous, the truth or the fiction?

Throughout the play, snippets of an American “ethnic tourist” are played on a screen above the stage. Turns out it is Gee, who Hwang sends to a remote Chinese village so he can have a first-hand immersion experience in the culture he so desperately wants to be part of. These villagers have never had Chinese outsiders visit, let alone a white American. Yet, after several months, they accept Gee into their community, sharing their most sacred treasure — music — with him.

Is Gee now Asian “enough?” Hwang uses this question as a powerful platform from which to launch many ideas and the soul searching queries they inspire.

What is the true litmus test — DNA ancestry or community acceptance? Is it what’s on the outside or inside that really matters? Is it how you see yourself or how others see you?

And how does this compare to religion, where there is no definitive physical barrier to joining a community and where its members can look like anyone and everyone? Is the logical extension of Hwang’s point about cultural appropriation an argument that religious conversion is impossible too? Although “Yellow Face” has its dramatic problems (a script in need of editing, actors in need of crisper direction, and a set that almost, but not quite, works), when a theatrical experience leaves me with a head full of ideas that linger long past curtain call, that’s a play I’m glad I saw.