“Book of Mountains and Seas” — Composer and Librettist –Ruo Huang. Director and Production Designer – Basil Twist. Presented by Arts Emerson at the Emerson Paramount Center, 559 Washington St., Boston, through April 21.

By Shelley A. Sackett

“Book of Mountains and Seas” is an artistically adventurous new work by award-winning composer Ruo Huang and MacArthur Fellow puppeteer/artist Basil Twist. Their collaboration is an inventive twist on ancient Chinese myths about creation and destruction that, in this perilous era of climate change, are especially relevant 2,500 years later.

The Chinese government released a series of stamps commemorating Chinese mythology, including the “Book of Mountain and Seas” stories, in the 1980s. Huang saw those stamps and never forgot the images. Four of them are the backbone of his production.

The vocal theater for 12 singers, two percussionists, and puppeteers is an abstract embroidery of sound, movement, and light. A troupe of puppets (handled by superb puppeteers) and the Ars Nova Copenhagen chorus turn Huang and Twist’s ingenuity into an unforgettable theatrical experience.

The performance is sung half in Mandarin and half in a language of the composer-conductor-librettist Huang’s invention, without English supertitles. Projected Chinese titles give the full text of the stories, but the English text is much briefer and its fade in much slower.

The 75-minute intermission-less oeuvre tells four timeless and abstract tales. The first myth, “The Legend of Pan Gu,” describes the creation of the planet. The program notes inform us that Earth is birthed from a cosmic egg that contains the hairy giant Pan Gu, who dies after 18,000 years of holding Earth and the sky apart. From his body spring the Sun, moon, mountains, rivers, animals, weather, and, finally, humans.

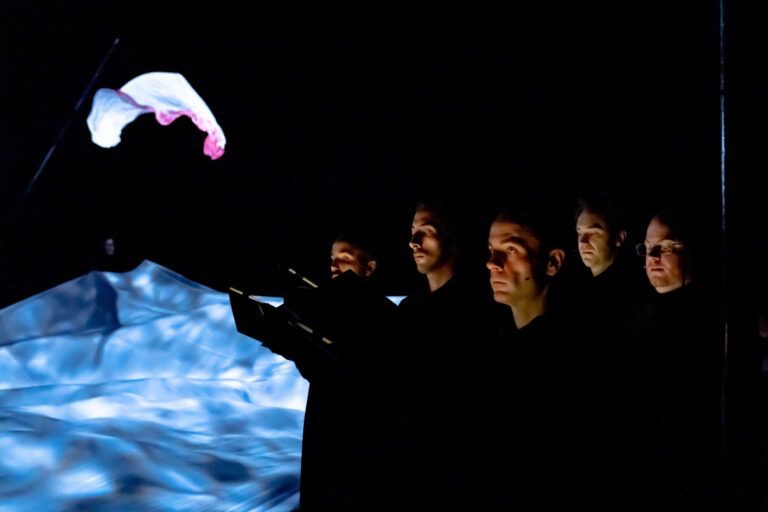

The show’s opening sets a spiritual tone, with a twelve-member choir with softly lit faces chanting an atonal primordial soup of notes that sound like church vespers. While there is little puppetry, the scene is set for the emergence of Kua Fu, whose face will be constructed from the pieces of bone-like driftwood scattered about the stage in the show’s final piece.

The ethereal, amorphous, and dissonant music matches the repetitive, slow movements on the background screen and on stage. Those who let go of expectations of linear storylines and dramatic action might enjoy entering a meditative state that is inspiring and nurturing. Others may find the experience boring and pretentious.

The second myth, “The Spirit Bird,” is about a princess who drowns at sea. Her spirit takes the form of a bird that spends the rest of eternity trying to take vengeance on the sea, filling it with pebbles and twigs.

The scene’s use of mottled lighting and undulating white silk for the sea and bird is simple and effective. Unfortunately, the scene is too long, and without the addition of any other imagery (other than a serpent who briefly swims by), the initial visual delight dwindles to the ho-hum.

In the third and fourth scenes, puppetry and drama replace repetition with excitement. “The Ten Suns” tells the tale of the ten Suns, children of heavenly gods. The ten siblings romp and play while taking turns lighting the Earth. When they decide to break this routine, and all go out together, their combined power dries up the Earth and wreaks climactic havoc. Only the intervention of the God of archery, who shoots and kills nine Suns, averts existential disaster. The lone remaining Sun, fearing his own demise, remains faithful to his duty, creating night and day.

With this tale, the show comes to life. Ten charming, anthropomorphic red rice-paper lanterns on slender stalks cavort their way across the sky. The music takes on a more harmonious quality, reminiscent more of early medieval music than a drone. As the Suns meet their fate one by one, sacrificed to save the Earth, the music marks the moment with a soulful but melodious elegy.

Finally, when the Sun-chasing giant Kua Fu appears in the fourth myth, even the most contemplative or somnambulant audience member will awaken and be utterly engrossed. “Kua Fu Chasing the Sun” is the story of a giant who sets out to chase and capture the Sun. Sadly, his quest ends in his dying from heat and exhaustion.

With the assemblage and appearance of the enormous puppet Kua Fu, it becomes apparent why there is a buzz about this show. Under the six puppeteers’ expert hands, the gnarly driftwood scattered across the stage comes to life with thrilling suddenness. Kua Fu’s head bobs, and his neck cranes. He acts and reacts. He runs and reaches. That this puppet exudes so much emotion while remaining abstract and clearly manipulated by humans is a testament to all involved in this show and worth the price of admission.

Lacking definable facial features, he can assume the persona of the gentlest giant or the meanest monster. Each audience member can call it as they see it, which is refreshing and fun.

Alas, the creature’s chase after the sun leads to his no less dramatic demise. White silk cloth again doubles as the sea as Kua Fu crouches on hands and knees and drains it in an attempt to quench his unquenchable thirst. He is dissembled with the same grace and charm with which he was created, his parts scattered once again across the stage.

When he dies, his walking stick falls to the ground, transforming it into a grove of peach blossom trees. Like spinning origami fairies, delicate confetti falls from the sky as the background shifts to a soft orange glow. It is a beautiful moment and an uplifting ending.

The one caveat before seeing this show is that unless you are a totally go-with-the-flow om shanti kind of person, a little context will go a long way. There are some shows where reading the program notes or reviews before experiencing the performance is a mistake. ‘Book of Mountains and Seas’ is not one of them.

Rather than interfering with the joy of forming an opinion based on visceral, in-the-moment reactions, even a brief intro will shed welcome light and might make the evening more enjoyable. Trying to read the too-light and too-briefly-displayed English script was annoying and distracting. An unsolicited suggestion to the team behind future productions: make the program notes available on the venue’s website.