‘Message In A Bottle’ — Music and Lyrics by Sting. Directed and Choreographed by Kate Prince. Music Supervisor and New Arrangements by Alex Lacamoire; Set Design by Ben Stones; Video Design by Andrej Goulding; Costume Design by Anna Fleischle; Lighting Design by Natasha Chivers; Sound Design by David McEwan. Presented by Sadler’s Wells and Universal Music UK Production with ZooNation: The Kate Prince Company at Emerson Colonial Theatre, 106 Boylston St., Boston, through March 30.

By Shelley A. Sackett

The only negative comment that anyone could possibly utter about the earth-shattering Message In A Bottle is that it is an unforgivable shame that its Boston run is a mere five days (seven performances). My suggestion is to interrupt reading this review, trust the reviewer, and jump on your computer to secure tickets while there might still be some left.

Yes, it really is that good.

Since Sting burst onto the music scene with The Police four decades ago, his eclectic styles, keen sense of lyrical storytelling, and hypnotic voice have earned him 17 Grammys, 25 American Music Awards, and 2 MTV Music Awards. He is known for his sociopolitical critiques as much as for his virtuoso musicianship.

Thanks to the virtuosity of British Oliver Award nominee Kate Prince (whose renowned narrative choreography includes West End theatrical hits Some Like it Hip Hop, Into the Hoods, and Everybody’s Talking About Jamie), 28 of Sting’s iconic songs have been transformed into the score for Message In A Bottle, Prince’s phenomenal newest production, which she created, choreographed, and directed.

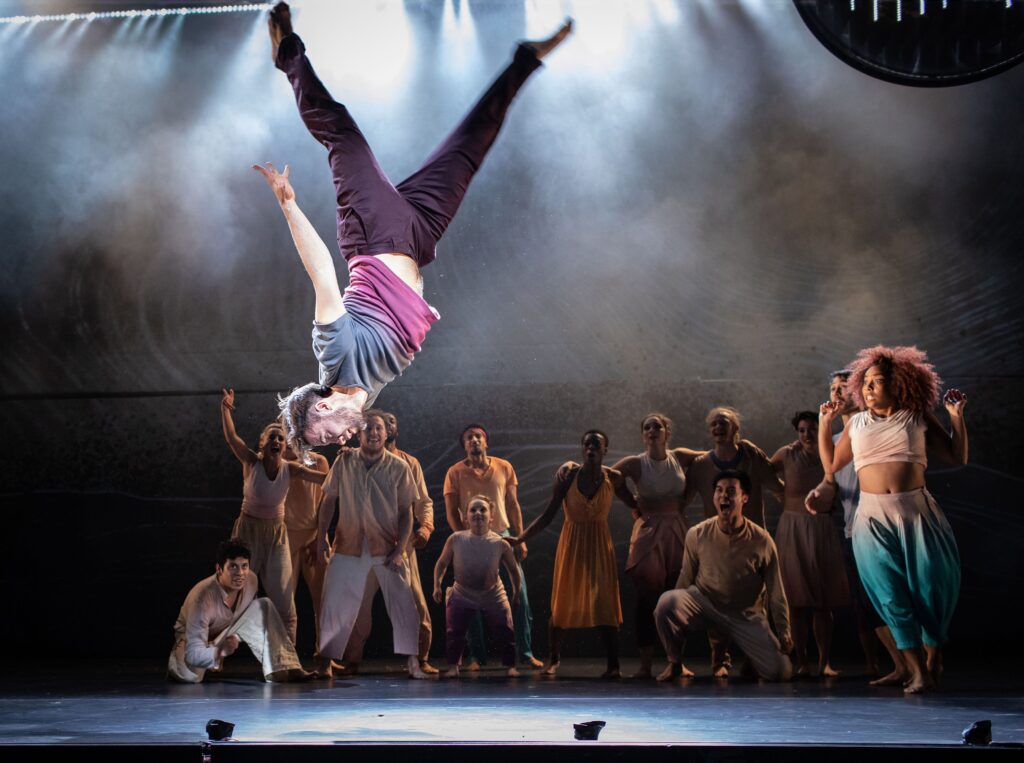

Master of hip hop, break dance, modern, swing, ballet, and street styles, Prince brings 23 members of her prodigious ZooNation dance company to daze and amaze their Boston audience with their flexibility, acrobatic prowess, and sheer stamina. At times, they seem to float in defiance of gravity, pure gossamer, and magic.

Prince’s storyline focuses on civil wars and the global migrant crisis they have spawned. Through the experiences of one innocent family (father, mother, and three teenage children) who become refugee collateral damage, she shows the wrenching toll exacted on these victims.

She uses Sting’s lyrics, the dancers’ prodigious acting skills, and first-class lighting (Natasha Chivers), set design (Ben Stones), costumes (Anna Fleischle), and video (Andrej Goulding) to narrate this emotional, full-length tale.

Even before the curtain rises, Message In A Bottle makes it clear that this is not simply a dance concert. Creative sparks are everywhere, starting with the opening song (“Desert Rose,” which inspired Prince to create the production) set against giant shadow silhouettes that mask dancers behind a gauzy drape. The drape lifts, revealing a minimalist but effective set with a huge screen backdrop that displays mood-altering graphics. A simple open box-like structure will shift use and mood throughout the production depending solely on how it is lit and how the dancers treat it.

We are thrust into the joyful, bustling thrum of a small village. People are happy. A man (the father) does acrobatic head dancing, then leaps and gyrates with superhuman speed and lightness. The dancers wear brightly colored costumes. There is a spritely playfulness in their steps.

Suddenly, bombs explode, menacing soldiers show up, and this peaceful community is peaceful no more. Violence and danger are now armed and in charge. Costumes change from primary to earthen tones.

Many villagers are sent to a refugee camp, where they are humiliated and tortured. Costumes again change, this time to gray, the benign box in center stage becomes a jail, and rape, pillage, and death are hinted at.

Sting’s “Don’t Stand So Close To Me” and the lyric “To hurt they try and try” are especially powerful and spot-on soundtracks.

Our family flees across the ocean on a flimsy raft, eventually having to separate to safer ground as strangers in strange lands.

“Rescue me before I fall into despair…I’ll send an S.O.S. to the world,” Sting sings as Act I ends somberly.

Act II is more uplifting, though to her credit, Prince does not tie it all together in a happily-ever-after bow. The daughter ends up in a Tahiti-like community where everyone wears long, billowy green skirts and offers her love, safety and a fresh start. Haunted by her trauma and missing her family, she nonetheless latches on and stays.

The two brothers find love, one in the arms of a man, the other in the arms of a woman. (ZooNation is a true company. None of the dancers have named headshots, so I can’t applaud them separately. However, the impossibly willowy blond who plays the bride is the production’s knockout standout.) The scenes of their rebound, with sensational pas de deux, are emotionally tender and artistically astonishing.

Although the siblings may never find each other again, the ending is hopeful; they are together in spirit. They have each found a new life that allows them to live in inner and outer peace.

It is not easy to describe the sheer miracle of this show. The 23 dancers move as a single unit, heaving and weaving in controlled yet casual waves as they leap, twirl, and use their limbs as organic punctuation. Yet individuals become recognizable, especially the blond bride and whirling dervish who play the father in the opening scenes. What a pleasure — and how noticeable — that Prince has brought members of her London-based company on the road with her instead of relying on a touring company to step into their impossible-to-fill shoes.

Prince’s choreography and direction are unquestionable genius. She (and dramaturg Lolita Chakrabati OBE) have woven together a contemporary story about the chaos and upheaval in the world as over 100 million people—more than half under age 18—are forced from their homes only to be greeted as unwelcome immigrants when they seek shelter elsewhere. And they have done it using the language of dancers’ bodies instead of spoken dialogue. The sheer dramatic power of this feat can neither be overstated nor overpraised.

The coordination of set, lighting, costumes, sound, and videography changes tone, place, and time in subtle and effective ways. The boat scenes, in particular, evoke what it would feel like to be at the mercy of both politics and roiling seas.

The lighting is organic, becoming a character that evokes woodcuts, rain, a prison, a love nest, and lush landscapes. In “The Bed’s Too Big Without You,” projected images and razor-sharp choreography and direction create a diorama that the audience can just slip inside.

While the dancers and the realness they bring to the stage can’t be overemphasized, the night really belongs to Sting, who re-recorded his songs for this production, many with female guest vocalists. He has had so many hits over the decades, changing genres and flowing from The Police to various musical partnerships and solo endeavors, that it is easy to forget what a brilliant songwriter and musician he is. Prince has cherry-picked the most perfect lyrics to narrate her story, and hearing this playlist elevates Sting’s work to that of a full opera score. Andrew Lloyd Weber can only be pea green with envy.

This show must be seen both because of its raw and relevant message and because it celebrates the extraordinary feats humans can achieve when they work together to create instead of to destroy.

For tickets and more information, go to: https://www.emersoncolonialtheatre.com