‘The Lehman Trilogy’ – Written by Stephano Massini and Adapted by Ben Power. Directed by Carey Perloff. Scenic Design by Sara Brown; Projection Design by Jeanette Oi Suk-Yew; Costume Design by Dede Ayite; Lighting Design by Robert Wierzel; Original Music by Mark Bennett; Co-Sound Design by Mark Bennett and Charles Does. Presented by the Huntington Theatre, 264 Huntington Ave., through July 23.

By Shelley A. Sackett

A lone and mournful clarinetist (Joe LaRocca) wanders across the stage of the Huntington’s theatrically astonishing “The Lehman Trilogy,” inviting comparisons in tone and content to the spirited drama “Fiddler on the Roof.” Steeped in ritual and Judaism, both stories trace what happens to a family when political oppression forces it to leave home, leading most of its members to emigrate to America.

For the dairyman Tevye ben Shneur Zalman, tradition and God are immutable and one; he will walk the straight and narrow walk wherever he wanders. For the Lehman brothers — and especially for their American progeny — tradition and God are moving targets, luxuries that morph with the exigencies of assimilation.

Yet the unobtrusive but ever-present LaRocca and his plaintive clarinet, saxophone, and flute melodies (original music by Mark Bennett) are constant reminders of the Lehmans’ past and the threads that, though frayed and denied, they share with Tevye and his ancestors.

“The Lehman Trilogy,” winner of the 2022 Tony Award for Best Play, assumes the 2008 demise of Lehman Brothers, the colossal bank whose collapse helped trigger the global Great Recession, is well known. Instead of rehashing that final piece of the story in detail, it wisely spends the bulk of its three and a half hours (two intermissions) chronicling the lesser-known details of the enterprise’s birth and extraordinary upward trajectory.

The action opens on 9/11/1844 with the New York arrival of 21-year-old Henry (Steven Skybell, the standout in a cast of standouts) from Rimpar, Bavaria. He immediately sets sail for Mobile, Alabama, with little but his experience in trade and finance and his skill with cloth. Buoyed to be in the American South, where Jews are allowed to own land and where the caste system is built on race rather than religion, Henry quickly makes enough money as a peddler to fund his move inland to Montgomery, where he settles down and opens a dry goods store. Younger brothers Emanuel (Joshua David Robinson) and Mayer (Firdous Bamji) soon follow to this promised land of milk and honey and cotton where “a man can live to work, not work to live.”

Absent the violence, restrictions, and family restraints of Rimpar, the brothers create their own American version of the Lehman myth, tradition, and legacy. Their unbridled ambition, ingenuity, and taste for fortune lead them to adapt to the times and fill any gap they spot.

The first Lehman Brothers sign is hung on a dry goods storefront that starts out selling fabrics and cotton and ends up as a powerful monopoly that buys raw cotton from antebellum plantations and resells it to factories in the North. The brothers ingeniously invent the profession of being a middleman, making their first fortune off the back of an economy dependent on slavery.

They also dip their toes into the business that will fuel their rise and fall. By offering credit to planters short of funds, they become cotton brokers, the first stage in their eventually becoming an investment bank.

Only after the cotton economy’s collapse in the wake of the Civil War do we hear a word of admonition or conscience about their connection to slavery (word is the lines were only added in response to criticism), and those are spoken by only one character, a local doctor.

“Everything that was built here was built on a crime,” he tells the brooding Mayer. “The roots run so deep you cannot see them, but the ground beneath our feet is poisoned. It had to end this way.”

Like a phoenix rising from the ashes, Lehman Brothers transforms and reinvents itself, helping the South as it reconstructs. Over the decades, it will survive two world wars, the 1929 stock market crash and the Great Depression, mutating from a brokerage house to an investment bank and finally to architects of subprime mortgages. The brothers relocate to New York and create the Cotton Exchange, Coffee Exchange, and Stock Exchange, all admirable strokes of business genius which pad their own pockets handsomely.

Structured in three parts, the play follows the Lehman family through 164 years of successive generations. We ride shotgun on the journey that proves even more tragic for the fabric and integrity of the heritage the three brothers so revered. Along the way, ethics, decency, and loyalty are qualities that vanish from the Lehman family tree, especially in the wake of the 1960s creation of a trading division run by non-family members. From boardroom savagery to talk of how to get people to buy things they don’t want with money they don’t have, the apples fall far, far from the ancestral tree.

And therein lie the bones of the play and the attraction of its world. At heart, this is a very human story about real, complicated people living real, messy lives. The story’s true tragedy and greater lesson is to be found in the degradation and demise of their familial — rather than financial — legacy.

When we first meet Henry, Emanuel, and Mayer in the 1840s, they are untarnished, wide-eyed boychiks, still tethered to their religious and family values. We bond with them. We root for them. Most all of, we care about them.

Henry is funny and sympathetic, his guilelessness rendering him accessible and charming. Mayer and Emanuel elicit similar reactions. When their children and grandchildren become characters from “Succession,” we cut them a little slack because we knew their parents and grandparents. Although we’re glad they’re not around to witness the havoc they wrought, we miss them.

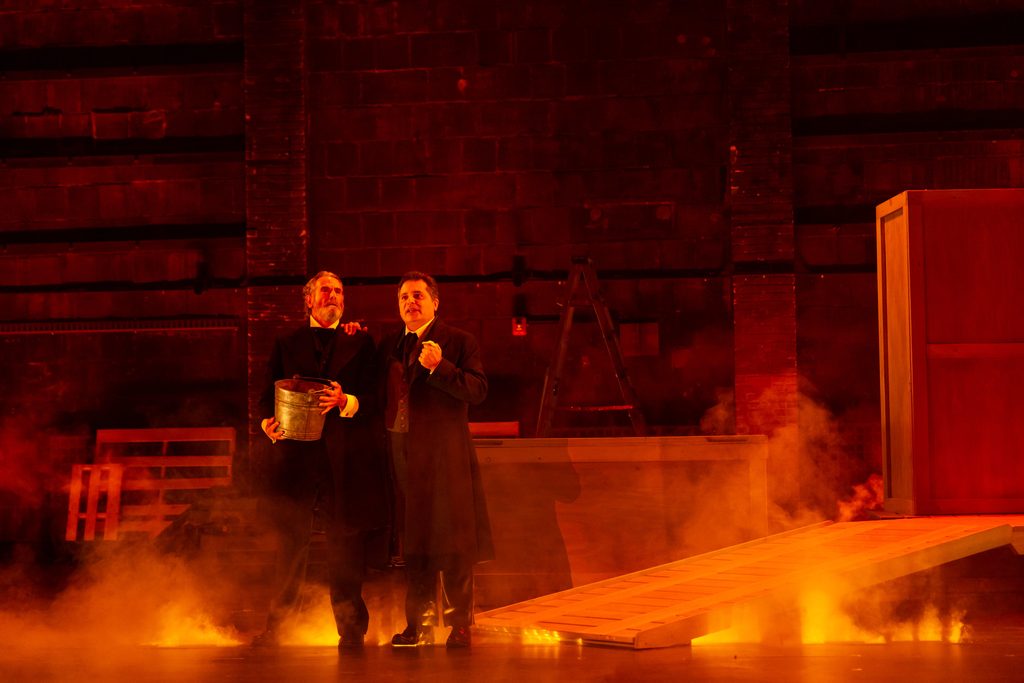

Fleshing out this compelling story is the real reason “The Lehman Trilogy” is in that rare not-to-be-missed category: the breathtaking three actors (the entire cast!) who switch genders and ages to portray a score of characters. Starting out as the engaging Henry, Skybell is a delight as a tightrope walker, a crusty, old rabbi, a flirty divorcée, and others. Bamji is no less extraordinary as the youngest (and patronized) brother Mayer. His acting chops are on full display as the ruthless Bobbie, a blushing bride, a pouty toddler, and more. As the steady, stalwart middle brother Emanuel, Robinson clearly enjoys the looser reins when playing the later Lehman clan members and their gang of motley plunderers.

Equally praiseworthy are Perloff’s razor-sharp direction (the wrecking ball pendulum as 2008 draws nigh is brilliant), Brown’s efficient yet thrilling set, and Oi-Suk Yew’s use of projected images.

Much has been penned complaining about the play’s underemphasis on the role slavery played in the Lehmans’ initial success and the short shrift given to the firm’s 2008 nosedive crash and burn finale. My take is that these were not intended as deliberate snubs. Rather, they were omitted because they were peripheral to playwright Massini’s core purpose: to allow us a peek through the keyhole at the tale of three German Jewish brothers from Bavaria and the way they took America by storm.

The resulting epic — intimate and engaging — is a nonjudgmental study of the personalities, relationships, and events that shaped this one family’s shifting definition of the American dream.

Don’t be put off by the play’s length. The story is so engrossing, the production (and acting!) so remarkable that more than one patron was overheard commenting that they wished it had been even longer! For tickets and information, go to: https://www.huntingtontheatre.org/whats-on/lehman-trilogy/