‘On Beckett’ — Conceived and Performed by Bill Irwin. Produced by Octopus Theatricals; Scenic Design by Charles Corcoran; Costume Consultation by Martha Hally; Lighting Design by Michael Gottlieb; Sound Design by M. Florian Staab. Presented by Arts Emerson at the Emerson Paramount Center, 559 Washington St., Boston, MA through October 30.

by Shelley A. Sackett

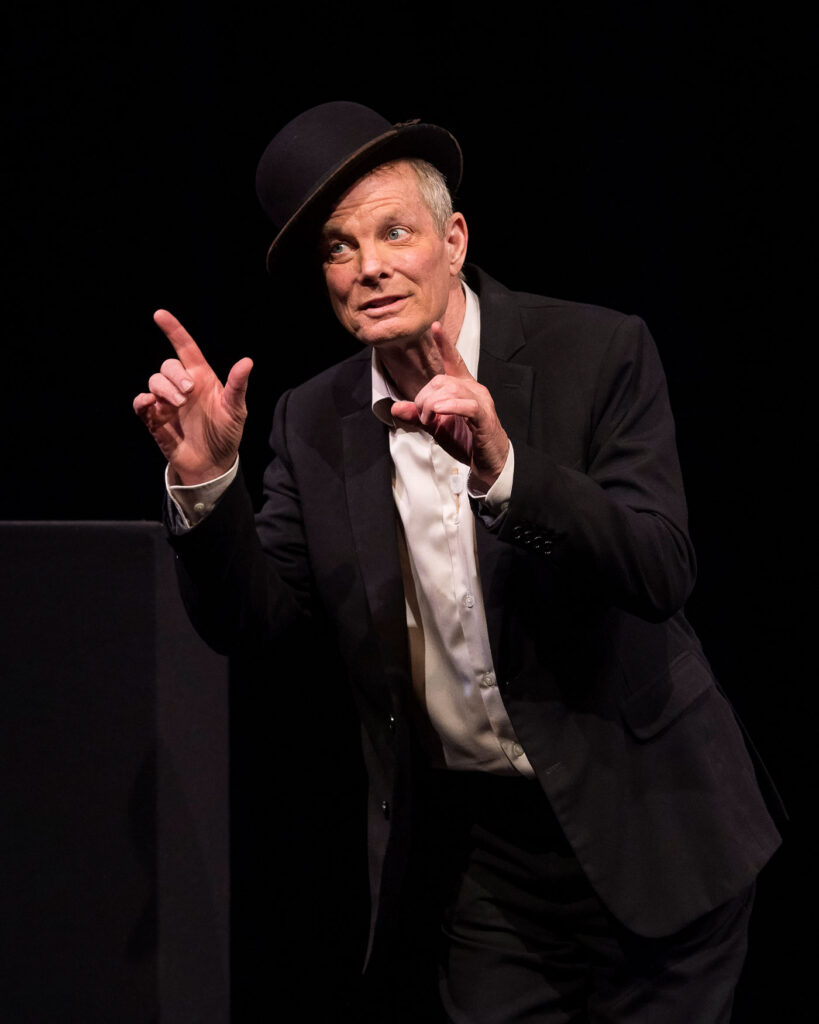

Bill Irwin is a legendary actor, writer, director and clown artist. The Tony award-winner is as known for serious theatrical roles on Broadway as he is for his beloved Mr. Noodle on television’s “Elmo’s World.”

With “On Beckett,” his solo exploration of his decades long relationship with the Irish playwright, Samuel Beckett, Irwin takes on yet another role — that of compassionate guide through the sticky wickets of Beckett’s intimidating and often baffling prose and plays.“Here is what I am proposing to you this evening,” he tells the audience with an intimacy and earnestness that has them in the palm of his hand from the get-go. “I’m not a scholar or a biographer,” he says almost apologetically, implying that those who expect a pedantic lecture from the head will be disappointed. “I am an actor and a clown and what I have is an actor’s knowledge” of Beckett, he says. And what a trove of treasures that is.

What Irwin brings to the table and generously shares is of far greater value and infinitely more enjoyable than a straight out lecture. He discloses what it has been like for him to experience Beckett’s language from the inside out, as one who has been entrusted with the sacred task of memorizing the writer’s words, processing them through his Bill Irwin persona, and then speaking them to a contemporary audience as he imagines Beckett himself intended.

For an absorbing, enlightening and entertaining 90 minutes, Irwin shines his inner light on four works by Beckett: Texts for Nothing, Watt, The Unnamable and Waiting for Godot. He peppers his readings/performances with anecdotes and observations, revealing what it feels like as an actor and as a human being to mouth the words of the great existentialist and arguably the greatest playwright who ever penned a line of dialogue.

His approach blends the physical (often hilarious) and emotional as he digs deep into Beckett’s “character energy,” managing to keep the evening challenging enough for aficionados of the work and light enough for novices. “These are like people I’ve known. Like my own mind — me, myself and I in conversation,” he says, bringing Beckett’s often lofty language down to earth.

Which is not to say he doesn’t pose heady questions meant to expand our thinking about Beckett, ourselves and the world we live in. “Was Beckett a writer of the body or mind?” he asks. Midway through the enjoyable and impactful evening, Irwin addresses the elephant in the room. “Is this a portrait of existence?” he asks of a passage in The Unnameable. “What is it?”

He then gives an easy-to-digest short treatise on existentialism, pithy and humorous, yet also the product of a deep thinker who has spent years pondering these questions both on and off stage. It is no surprise to learn he has won Fulbright, Guggenheim, National Endowment for the Arts and MacArthur Fellowships. His explanations and analyses are brilliant. “These are the precise but undefinable questions that keep us awake,” he says before adding,” and put us to sleep.”

As expected of a lauded actor and director, his timing and punctuation is perfect. But Irwin is also a clown, and when he grabs his bowler and baggy pants, the evening shifts gears. Although Beckett’s words carry no less weight and Irwin’s performance embodies that gravitas, it is now clothed in the shimmering gossamer of physical comedy, taking the sting out of some of the words by allowing us to laugh at them and, by extension, at ourselves. Sure, existence is tough and death is even tougher, but let’s not forget that we were also created to laugh, Irwin reminds us.

Irwin appeared with Steve Martin and Robin Williams in the Lincoln Center Off-Broadway production of Waiting for Godot in 1988, in the role of Lucky. Lucky’s only lines consist of a famous 500-word-long monologue, an ironic element for Irwin, since much of his clown-based stage work was silent.

He treats us to a remarkable rendition and, at the end of the show, frankly admits that even after all these years, some of Beckett’s language remains beyond his grasp. “I keep discovering new things in the words,” he says. “I don’t know why. I don’t know how an airplane stays up in the air either, but I still want to climb onboard.”

Act NOW and you might just be lucky enough to catch one of the last Boston performances. Whether you’re encountering the Nobel Prize winner’s writing for the first time, or building on a body of Beckett knowledge, this dynamic showcase is not to be missed.