by Michael Cox

Common Ground, Revisited – Co-conceived and adapted by Kirsten Greenidge; co-conceived and directed by Melia Bensussen; set design by Sara Brown; costume design by An-lin Dauber; lighting design by Brian J. Lilienthal; sound design by Pornchanok Kanchanabanca; projection design by Rasean Davonté Johnson; wig/hair and makeup design by J. Jared Janas; dramaturgy by Neema Avashia; stage-managed by Emily F. McMullen. Co-produced by The Huntington Theatre and ArtsEmerson at the Calderwood Pavilion/BCA through July 3, 2022.

When a group of people have no voice in the conversation, they interrupt. They make their voices heard through disruption. Colonial Boston did this back in 1765 when we enacted the first public act of defiance against the King of England and rioted in the streets, and we continued the tradition in the 1970s when U.S. District Judge Arthur Garrity Jr. ordered Boston to implement race-integrated busing.

In Common Ground, Revisited, The Huntington Theatre Company looks at the non-fiction book Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families, a Pulitzer Prize-winner which in many ways has come to define this city – because it disrupted us. It asked us to look in the mirror and examine – in microscopic detail – our racism.

For around a decade, Kirsten Greenidge and Melia Bensussen have been exploring this book with the goal of making it into a piece of theatre. The book exhaustively examines Boston during what we euphemistically called “the troubled times,” the years in and around the Civil Rights Movement. Those times are still with us, the play argues. The disparities of those times are as great as ever because we are as broken as ever. We don’t have equality; we haven’t ended racism and we haven’t solved anything. We just have new vocabularies and a new excuses.

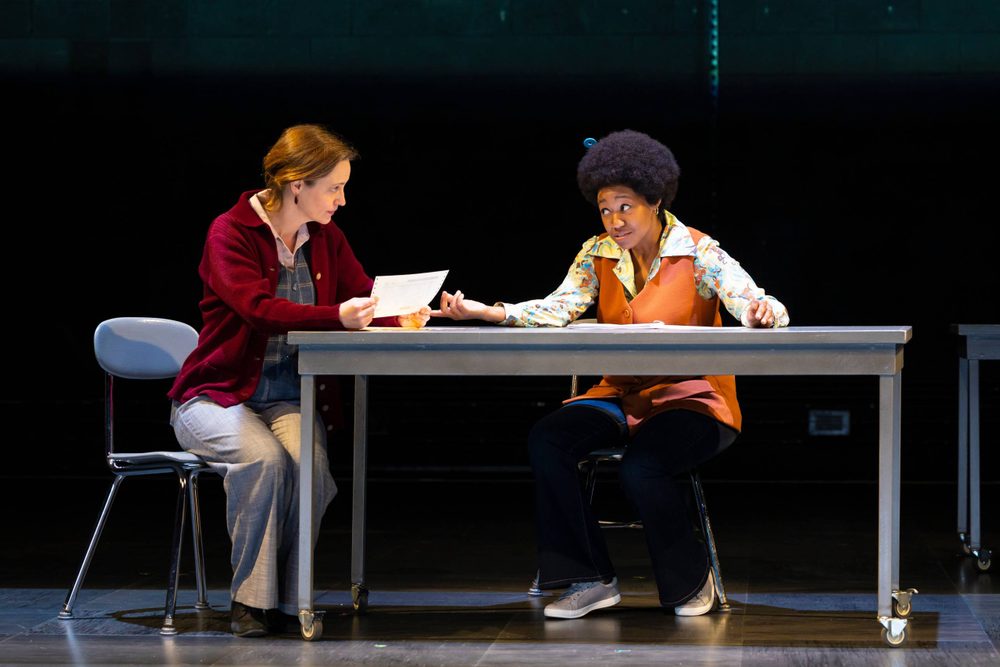

The play starts simply enough with an exchange between two high school girls who pass each other in the hallway. One girl, Lisa McGoff (Marianna Bassham) is white and the other, Cassandra Twymons (Elle Borders) is Black. Lisa is aggressively friendly, even calculatingly political. Cassandra reacts with necessary apprehension. We don’t have any context at this point, but we can see that the moment is fraught with subtext, a past, unresolved tensions. We will later find out why. This is a Charlestown public school in the 1970s. These smart, savvy young women have been thrown into an arena by their parents and leaders, and each girl is expected to fight.

This scene between Twymons and McGoff is a straightforward representational scene (the actors ignore the audience and play characters that are pursuing a goal) and Borders is particularly adept at this kind of acting. Her palpable ambiguity makes the audience ask all kinds of questions. Who is this person? Why is she so skittish and what is the relationship between these two young women?

At this point we have every expectation that the play will remain representational, but then the walls fly open. Literally. And an ensemble cast of 12 actors end the representational performance and address the audience directly. Each actor plays a nameless character which will narrate the action of the book directly to the audience, while also taking on the persona of several different non-fictional characters, actual people Lukas reported on in his book.

Unlike most plays, this is an overtly didactic piece of theatre. Rather than focusing on the ambitions and obstacles faced by particular characters, the play spends the majority of its time focused on the politics at hand. Traditional drama follows the desires of individuals who will usually change or evolve by the end of the play. But this is based on non-fiction so the playmakers have chosen to convey the subject with non-Aristotelian drama. In this, the idealistic wants of the individual are subservient to the material ambitions of society at large.

To highlight the local subject matter of this play, the cast is comprised of local actors, people we’ve seen time and again on the Boston stage, as familiar to us as the people we see around the neighborhood. Folks like, Karen MacDonald, Omar Robinson, Michael Kaye, Stacy Fischer, Shanaé Burch, Kadahj Bennett and Amanda Collins. Matthew Bretschneider was clearly cast for his physical acting and his ability to slip easily from one distinct character into another. And Maurice Emmanuel Parent was cast because… well obviously he’s amazing and the Huntington was lucky enough to get him.

The set design by Sara Brown evokes a particular type of Modernist Bostonian classroom, the kind of architecture that reflects a belief system more than an aesthetic. Think the McKinley School or Blackstone Elementary in the South End. The values of this architecture are simplicity, honesty and equality. (It’s critics would associate it with totalitarianism and urban decay.) Conveniently, it offers a lot of blank spaces for Rasean Davonté Johnson’s projections, which consist of a good deal of black and white historical photography.

The issues of race-integrated busing are largely neutralized today, so why is Common Ground relevant? We are so fond of believing that Boston doesn’t have the issues of the rest of the nation. “Boston is the sane part of this country.”

This is the capital city of the state that first outlawed slavery. This is the is the state that Frederick Douglass called the land of hope and a beacon for the Black person. This is the city where abolitionists took on Federal marshals when they came here to gather up formerly enslaved refugees, and in 1855, where Black people sued the government and won, because we recognized the fact that they deserved an equal public education. How could we be racist?

The tumult surrounding race-integrated busing forced Boston to face the fact that we were as segregated anywhere else in the nation, perhaps more so, but Boston’s segregation had nothing to do with water fountains and bathrooms. Boston’s segregation was all about geography. Bostonians stuck to their neighborhood and the neighborhood in this city are defined by race. Italian people lived in the North End, the Irish in Charlestown and South Boston, Black people lived in Roxbury, Jewish people in Brookline, Asians in Chinatown and, of course, the Brahmans lived on Beacon Hill. It wasn’t that Bostonians were trying to segregate their public schools — schools were segregated because Boston neighborhoods were so insular.

Lawmakers tried to desegregate public schools by bringing people of differing races together, integrating us and giving us the opportunity interact and learn from each other. But busing children into schools outside their neighborhoods inconvenienced people, and the people this affected — both Black and white people — disrupted. They broke into the conversation and they did it with racial slurs and racial violence.

How could such an enlightened city react with such ignorance? It’s important to reflect on this question because Boston thrives on education and inequality thrives in Boston’s educational system. Today Boston public schools are primarily non-white because no one will attend a public school who can afford not to. In the city that founded the first public school in the nation, public schools are regarded as the first step on the roadway into the working class.

What is the American Dream if not the promise that every individual has the opportunity to rise above her/his/their station and excel in this nation? But this is simply not and never has been the case. Common Ground Revisited disrupts that notion, and forces us to address the latent racism that lurks quietly — for now — underneath the surface of our enlightened city. For more information and tickets, go to: https://www.huntingtontheatre.org/whats-on/common-ground-revisited/